“I dig down into the sewer pipes and drains to show Americans what their problems are.”

This article appears in AdHoc 26. To subscribe to our quarterly zine—and receive other AdHoc-related goodies—become a member.

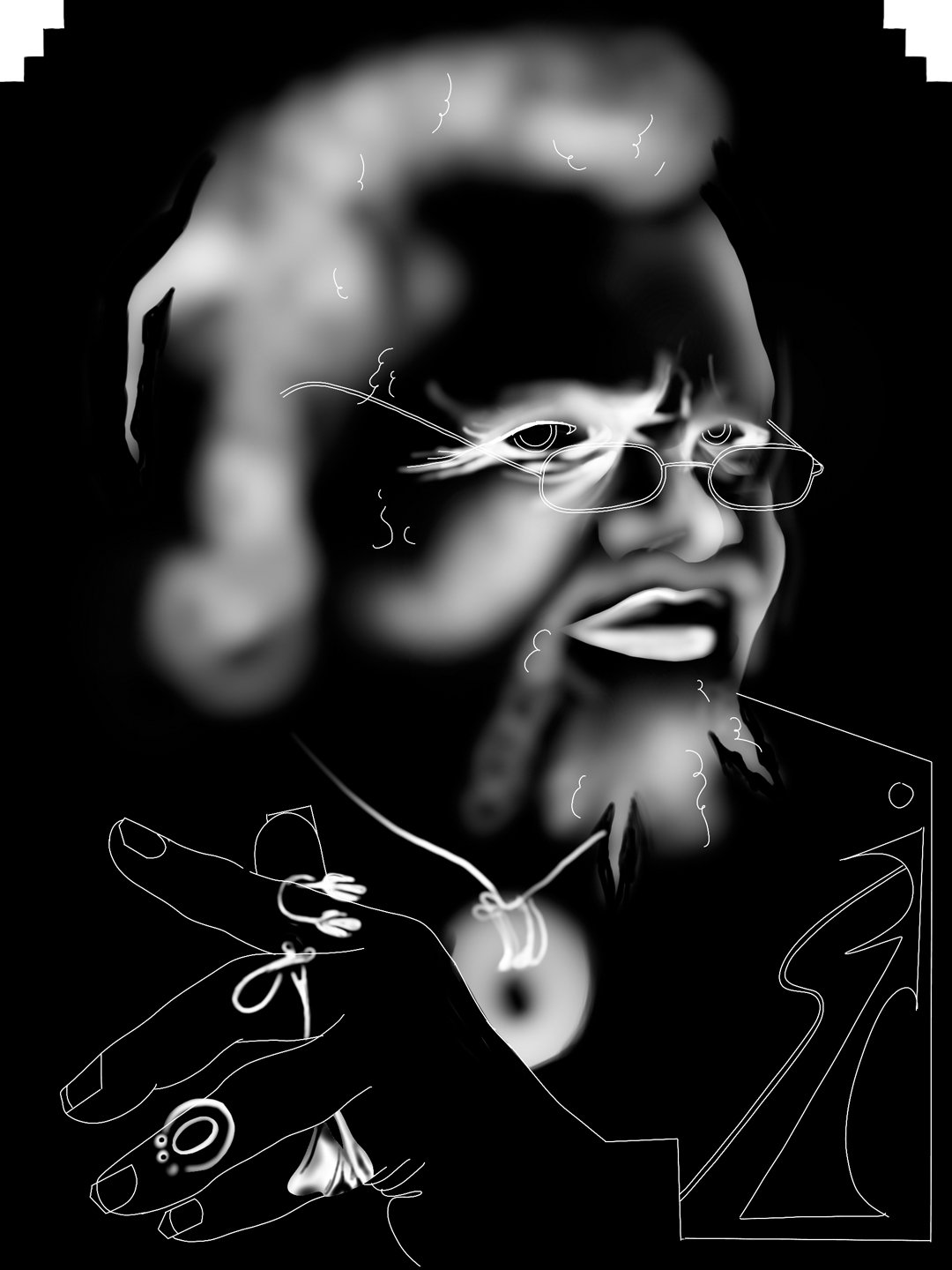

Lonnie Holley is the type of person who should need no introduction, but because there is no justice in this universe, here it is. The 68-year-old, Alabama-born artist takes mundane objects that on their face seem antiquated, broken, or cast-aside and reassembles them into works that reveal the symbols and structures undergirding the American cultural imaginary. “Break down a word with me, make over the world,” he sings in “I Woke Up in a Fucked Up America.” The video for the song features shot after shot of Holley’s creations, including a figurine patriotic eagle confined to a bird cage, nearly drowning in shotgun shells. (For further proof of his brilliance as a visual artist, scroll down to cover of the new AdHoc zine at the bottom of this post, which features one of his woodcuts)

Long a fixture in Atlanta’s underground art world, Holley came to music relatively late in life, releasing his first full-length, Keeping a Record of It, in 2012. In September, he released his third record, Mith, on indie heavyweight Jagjaguwar. While the record retains his loose, improvisatory lyrical style, Mith finds Holley making a quantum leap forward musically, eschewing the home-made feel of his previous work for a full-band extravaganza, with the assistance of producers Richard Swift and Shahzad Ismaily. Holley whistles over warped Americana, sings sci-fi ballads over taut drones, and spins parables of racial injustice and the impending doom of our climate over industrial-strength noise. Imagine a jam session between Sun Ra, Gil Scott-Heron, and Nat King Cole, and that’s Mith—except that his actual collaborators for this one include avant-garde jazz outfit Nelson Patton and new age icon Laraaji.

AdHoc spoke with Holley over the phone from an artist’s retreat in Oregon. Holley spent the conversation puttering around the woods while revving his rhetorical engine, riffing on snatches of my questions as well as the objects in front of him. At times, it felt less like I was asking Holley questions and more like I was providing him with the raw material for a linguistic sculpture—one that spanned environments both natural and manmade, animals, robots, ancestry, and Holleyisms such as “Ollywoods” and “Ologies.” Our conversation was just as confusing for me as it may be for you to read, but then again, Holley communicates best when he’s creating art, and art can be confusing as fuck. When it comes to Holley, though, even the nonsensical feels deeply profound.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

AdHoc: The record is fantastic.

Lonnie Holley: Well thank you, that’s what we were going for.

It really does a great job of capturing this mood of what it’s like to be alive in the world these days.

We’re living in a world where as we change, we’re changing the environment. We weren’t taught to notice that.

You were born in 1950. How has the world changed since then?

We had Hollywood and Bollywood and Ollywood, but all those places weren’t giving us all that we needed to know. We saw how humans were using wars to obtain lands for migration, but we didn’t see what actually having those wars—especially when we got to the part of using “da mite,” as in dynamite and explosives—[was going] to do. I’m seeing the devastation of these fires. After the fire, I’m seeing them trying to cut trenches to keep the fire from burning any person, but now with the rain coming in or snow season… Snow is going to blanket the whole thing. Snow is going to melt. The melting is going to cause runoff. It’s going to start from up high and run down low, so this runoff will try to create its own river to run in. Just when you think we’re out of this danger, we’ve created a more dangerous situation. [They say,] “But that’s for another time! I can deal with it when it comes.” No, we can’t! We can’t always deal with it when it comes. And that’s what I’m trying to sing about.

In your art, you often take everyday objects and recontextualize them in very poetic ways. Your lyrics do this as well—when I was listening to your new record, I wrote down the phrase “machinery, technically designed.” It’s an everyday phrase, but the way you say it really stuck with me.

Robotically, we are dealing with the digital, and the only way that the digital is going to be processed or programmed to help humans is going to be done musically. That’s the only way that you get humans to participate.

In your opinion, how can people learn to come together and help each other instead of fighting all the time?

They learn to come together by going to museums.

Your work is in museums now.

For a long, long time, my work was looked at like it was too dirty to be in a museum. I dig down into the sewer pipes and drains to show Americans what their problems are. We are going to need better drainage systems, because this water sits and it rushes in and it drowns things. This humidity, this precipitation, is drawing a moisture through the air so that things—big machines—sweat. Think about the electrical currents that they pull. Think about the wires themselves. I don’t know if you’ve ever had a heater and felt how hot the wires carrying the currents get, but think about the box that the currents are coming from. You got one little square box with fifteen thousand little things hooked up, and nobody investigates the heat of that one box itself. I’m telling some truth that puts people to work, and people don’t like to work.

I think if you’re asking, “Lonnie do you have anything to do about architecture?,” then yes, I think I do. My work has something to do with architecture, archaeology, biology—I deal with all of the “ologies.”

I feel like you really deal with the world as you interpret it.

I try to, I really do. I’ve been talking so much I haven’t given you a chance to ask me any of the questions that you need to ask.

That’s totally fine. I like to let the conversation go where it goes, and eventually you get to everything you want to talk about anyway.

I deal with things, from the fabrics that humans wear, to the household items and the construction materials. [Historically], if you look at what people built their homes with, they put a lot of thought in building those homes, but also you gotta remember, they was building those homes with an understanding of winter and summer. They built something that could be taken apart when it needed to cool down, and they could increase warmth for the winter. There was so much that was layered in our grandmothers’ and great-grandparents’ behavior and use of materials. I am more like the grandparents. I grew up learning more from my grandparents than I did my parents, because my parents were living in a much more lighter, less complex way.

What’s the earliest memory that you can recall?

I really loved the ditch and the creek. I remember going up and down the creek, turning over the glass, turning over the stones. I lived by a state fairground. The drive-in theater was half in my backyard. Right around the corner, maybe two-and-a-half blocks away, was the place that made the big industrial sewer pipes. Big, huge things. I got a chance to examine these big pieces of stone. I loved it.

What do you think of New York?

It’s just not the same. The steel that was buried in the earth a hundred years ago—that’s nothing but eggshells now. You can almost take a board and knock all of New York down. I’m scared when I’m up there. I’m scared when I’m on the coastlines of California. I’m scared right here, because of the fires that are starting. I’m scared of the animals that are running away from the fires, the creatures and things. You got a lot of creatures, creepy-crawlies, snakes, all the way up to all the four-legged runners.

I’ve heard that in Oregon, where you are now, climate change is causing otters to move to the state and deplete the salmon population.

If the beavers are running away from the fires, you gotta get them a new feeding ground. Now you got this big area—it’s almost like a pot of gumbo, you know what I’m saying? The lakes are turning into a pot of gumbo, especially with all this stuff that’s gotta be dropping diseases. My friend was saying he needs a gas mask [to go outside,] because the smoke and ashes are so thin we can’t see. The song “I Woke Up in a Fucked Up America” isn’t about politics. It’s about the environment—the stuff we have on top of the earth that’s easily ignited, the stuff we have out on the ocean in shipping containers that we know nothing about. The ocean becomes like a mirror, reflecting the sun. We’re riding a microwave.

What does a person need to do to live an honest life?

Study. Without study, we cannot become better people. Without study, we cannot work. If you don’t have no money for education, teach yourself. You got libraries, you got materials that you can just pick up and think about. Try to understand their contents and their values. Just don’t sit around. I understand that HDTV is feeding us more information now, but HDTV is like a microwave. While you’re sitting on the couch, you’re being cooked. Every day, you train your brain to want to see the next episode. We need to get away from that to get the earth right.

When you were making the record, how did you decide which songs to keep and which ones to cut?

It was a collaborative effort. I’ve gotten the opportunity to see the earth more. I got a chance to see the castles. I got a chance to go places where someone like Jesus would have walked. I have been where wars happened. I have been to the gate of the wall. If they build a wall, somewhere in society, they’re going to say, “Tear down this damn wall!”

When I think about history, I get this sense that things are moving forward while constantly repeating themselves. It’s the same patterns but with different clothes, different technologies, different words.

Words, words, words. Take the word “word” and break it down. I did a piece when I was in Europe called “Never Off the Pedestal.” It was about Shakespeare using his words to make other words, and seeing how thoughtful and emotional those words were. Now people are actually studying his words, and one day they are going to study my words and make grand plays. To be or not to be? To do the word, or just let the word be itself.